Data initialization

The first part of the run() method should be data initialization. It already contains a bit of code, which are:

- Loading shaders, initializing uniform locations

- Creation of projection and view matrix

- Setup GL state for 3D rendering

Our goal for this part of the tutorial is to implement things related to glTF data. We'll come back later on the previous points.

Loading the glTF file

The part to replace in this section is

// TODO Loading the glTF filewith a call to the method that you must implement.

The path to the glTF file is stored in the member variable m_gltfFilePath.

A glTF file is a json file describing the scene. It references other files for large data: binary files for geometry data, and image files for textures.

We use the tinygltf library to load the glTF data. This library is included in the project SDK.

Implement glTF loading

- Read the example code of tinygltf

- Use it to implement a method

bool loadGltfFile(tinygltf::Model & model)in theViewerApplicationclass.- This method should use

m_gltfFilePath.string()to load the input glTF file into themodelpassed as reference. - The method return value should correspond to what

tinygltfreturns. - If there are errors or warning, print them.

- You don't need the implementation part shown at the begining of the example: it is already done is the

tiny_gltf_impl.cppfile of the SDK. But you need to include thetiny_gltf.hheader everywhere you usetinygltf::prefixed symbols.

- This method should use

- In the

run()method, define atinygltf::Modelinstance and call your method on it. - Compile (with

cmake_build) and run your code on a test model (withview_helmetorview_sponza). You should still see a black screen, but no error. - Commit and push your code.

- If you are struggling, check the solution

Understanding glTF data

The glTF format is defined on its dedicated repository. No other resource is needed to understand and use the format.

The first file to look at is the quick reference card. It gives a large overview of how a scene is described by a glTF file.

To get more details about a specific part you can read the specification: https://www.khronos.org/registry/glTF/specs/2.0/glTF-2.0.html. Use CTRL+F on this file to quickly find what you are searching for.

The tinygltf library define the tinygltf::Model class to store a glTF file content. The json fields such as buffers, nodes, etc. that are mentionned on the glTF specification are mapped to attributes buffers, nodes, etc of the class. However it may happen that the names chosen by the writer of tinygltf are not exactly the same as the ones in the specification. For example, the scene json field is stored as the defaultScene attribute in the class.

Set up your resources:

- Keep the quick reference card open in a browser tab.

- Read and try to understand the sections "Concepts", "scenes, nodes", "meshes" and "buffers, bufferViews, accessors". We will focus on these on the next sections.

- Keep the

tiny_gltf.h(underthird-party/tinygltf-*) file open in a tab of your code editor. Consider it as your documentation to manipulatetinygltfdata. - Keep the OpenGL documentation open in a browser tab. You'll likely need it.

Buffer Objects and Vertex Array Objects

To understand the close relationship between glTF data and OpenGL, a reminder about Vertex/Index Buffer Objects (VBO, IBO) and Vertex Array Objects (VAOs) can help.

To be rendered on the GPU, geometry data is stored in buffer objects. Buffers objects correspond to buffers allocated on the GPU's memory, for quick access by the GPU.

A buffer object can be created with the following code:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Here we use glBufferStorage instead of glBufferData, which could also be used. The difference is that once a buffer has been allocated with glBufferStorage, you cannot change its size anymore. Knowing the buffer will remain the same size might give to the driver the opportunity to do some optimizations.

Similarly we can create multiple buffer objects and fill them with a loop:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

For clarity, we call a buffer object used to store vertex data (positions, normals, texture coordinates, ...) a vertex buffer object (VBO) and a buffer object used to stored index data an index buffer object (IBO).

OpenGL can't do anything with buffer objects: they are just bytes of data for OpenGL. Like a void* and a byte size would just be a pointer to an area of memory with a specific size. We can't do nothing with it if we don't know the structure of the data inside.

For OpenGL to correctly interpret the data, we need to describe its structure. And for that we use Vertex Array Objects (VAOs). A VAO is used to describe the data of a primitive to draw (a primitive can be composed of triangles, points or lines). A primitive is described by its vertices, and each vertex is defined by vertex attributes.

So the VAO of a primitive describes:

- What vertex attributes (position, normal, ...) are enabled. Each one identified by an index (that we generally choose based on our shaders, more on that later).

- For each vertex attribute, what buffer object store its data, and how to read it (what type, how much components per attribute, where the data starts, how much bytes there is between 2 attributes).

- If the primitive has indices, what buffer object stores the indices and what is the type used (uint8, uint16 or uint32).

Now it is up to us to decide how we split our data in buffer objects:

- Should we use one or multiple buffer objects for our vertex attributes ?

- Should we pack or interleave the data ?

For our application, we actually don't really care: we will just follow what the glTF file tells us.

Here is a piece of code to create a fill a vertex array object:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 | |

Keep the documentation http://docs.gl/ open because you will likely need it.

Relationship between glTF data and OpenGL data

If you look at the part "buffers, bufferView, accessors" of the quick reference card or glTF, you might start to notice some connexion with VBOs, IBOs and VAOs.

A good way to vizualize the relationshop between buffer, bufferView and accessor is to use the glTF-Sample-Models repository. For simple models they provide a picture illustrating the data layout, look at the end of each page:

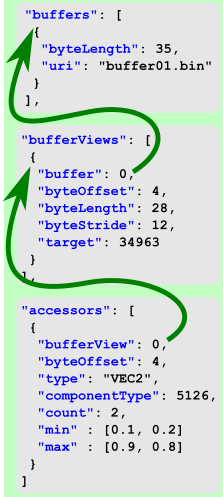

For reference, here is the image from the quick reference card:

The "buffers" stores a list of buffer, each one containing the data that must fill a buffer object. With tinygtlf we can access model.buffers[i] which has type tinygltf::Buffer.

A tinygltf::Buffer has a member variable std::vector<unsigned char> data. So we have model.buffers[i].data.size() which is the "byteLength" field of the i-th buffer defined in the glTF file, and model.buffers[i].data.data() which is a pointer to the raw data loaded by tinygltf.

You can notice the unsigned char type used for the vector. An unsigned char is 1 byte of data (from the C specification), so it basically mean that we have a buffer of data but we don't really know what is inside, how to read the data, exactly like the GPU for a simple buffer object.

Then we have "bufferViews", storing a list of buffer views. You can see it looks like this in json:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Ok this look a bit like a part of a Vertex Array Object. We have the index of a buffer to bind. This index refers to an index of the array in model.buffers.

The strange "34963" correspond to a binding target for the buffer. Here is is GL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFER (if you print it in your program you'll see the value is indeed 34963), so the buffer view must correspond to an index buffer object.

The other parameters look like some parameters we pass to glVertexAttribPointer. Remember the prototype:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

However we miss some arguments. To fill the gap we have the concept of "accessors". Lets take look on the example from the quick reference card:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

This seem to describe the missing parameters, more or less. Again the strange 5126 correspond to a OpenGL enum. Here it is GL_FLOAT (meaning that the example of the quick ref card is invalid: the accessor tells we have float data, but the bufferView ask to bind it GL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFER, which is basically invalid because we need integer data on GL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFER).

The byteOffset of the accessor must be combined with the byteOffset of the buffer view to get the last argument of glVertexAttribPointer.

The type and componentType should be used to compute "size" and "type" parameters. For that we can thank tinygltf because it parse them and gives us "accessor.type" for "size" (wtf ?) and "accessor.componentType" for "type".

What about the other parameters ? "count" is the number of values to read from the buffer view and we'll be used at render time to specify the number of vertices to draw. "min" and "max" are here to get bounds on the data and normalize it if we want (we won't use them).

OK, this is a bit complicated, but we have the following relationship:

- glTF Buffer <-> OpenGL Buffer Object

- glTF Buffer View + glTF Accessor <-> part of OpenGL Vertex Array (only describe one vertex attributes)

To get all vertex attributes, we need to look at the "meshes" section of the quick reference card, we have this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

This tells us that a mesh is defined by a list of primitives. In a given primitive we have: - "mode", again a GL enum that correspond to GL_TRIANGLES, GL_POINTS or GL_LINES - "indices", the index of an accessor that must be used to obtain indices of the primitive. It is optional, and if not present the primitive has no indices. - "attributes", an object with a field for each vertex attribute composing the primitive. All are optional. The index specified for each one is the index of an accessor that must be used to get the vertex attribute data. - "material", we don't care for now but we'll use it in a later part of the tutorial

All possible vertex attributes are defined in https://www.khronos.org/registry/glTF/specs/2.0/glTF-2.0.html#geometry. We will focus on POSITION, NORMAL and TEXCOORD_0 for now.

The complete relationship is: - glTF Buffer <-> OpenGL Buffer Object - glTF Buffer View + glTF Accessor + glTF Primitive <-> OpenGL Vertex Array

This tells us how to build our OpenGL Data from the glTF Data. It can be a bit complicated to implement because we need to keep track of many vector indices (there is many indirections). That is why we need to use good explicit names for our indices, and not just "i" or "j". If you don't, you will become crazy.

Creation of Buffer Objects

The part to replace in this section is

// TODO Creation of Buffer Objectswith a call to the method that you must implement.

We start with the easy one: converting glTF buffers to OpenGL buffer objects. This is easy because we have a direct mapping glTF Buffer <-> OpenGL Buffer Object. What we need to do:

- Create a vector of GLuint with the correct size (model.buffers.size()) and use glGenBuffers to create buffer objects.

- In a loop, fill each buffer object with the data using glBindBuffer and glBufferStorage. The data should be obtained from model.buffers[bufferIdx].data.

- Don't forget to unbind the buffer object from GL_ARRAY_BUFFER after the loop

This code will look like the Buffer Object example code from before.

Implement a method std::vector<GLuint> ViewerApplication::createBufferObjects(

const tinygltf::Model &model) that compute the vector of buffer objects from a model and returns it. Call this functions in run() after loading the glTF.

Check compilation, run, commit and push your code.

Creation of Vertex Array Objects

The part to replace in this section is

// TODO Creation of Vertex Array Objectswith a call to the method that you must implement.

Now the hard part. Honestly, once you succeed to implement this part and understand it, you should understand glTF (and more generally: indirections).

Start by adding en empty method std::vector<GLuint> ViewerApplication::createVertexArrayObjects(

const tinygltf::Model &model, const std::vector<GLuint> &bufferObjects, std::vector<VaoRange> & meshIndexToVaoRange);

This method is supposed to take the model and the buffer objects we previously created, create an array of vertex array objects and return it. It should also fill the input vector meshIndexToVaoRange with the range of VAOs for each mesh (see below). This vector will be used later during drawing of the scene.

In the function declare std::vector<GLuint> vertexArrayObjects;

This vector will contain our vertex array objects. Take note that I don't give a size, because we don't know it yet.

Indeed, we should have a VAO for each primitive of the file. But the top level description of geometry is made with "meshes". And each mesh can have multiple "primitives". So the only way to know the total number of primitives (and thus of VAOs) is to loop over the meshes and add the number of primitives of each one. But we won't do that. We will loop, but use resize() to extend the vector as required at each loop turn.

Create a loop over meshes of the glTF (model.meshes). Extend the size of vertexArrayObjects using resize(), by adding the number of primitives of the current mesh of the loop (model.meshes[meshIdx].primitives.size()). Push back the corresponding range of vertex array objects in meshIndexToVaoRange (see code below).

Here you need to understand that vertexArrayObjects will grow of model.meshes[meshIdx].primitives.size() elements at each loop turn. At turn meshId - 1 we have const auto vaoOffset = vertexArrayObjects.size() elements. Then at turn meshIdx we call resize that way:

1 2 3 | |

The VAOs for are new primitives span the range [vaoOffset, vaoOffset + model.meshes[meshIdx].primitives.size()]. We need to call glGenVertexArrays on this range of data to create our VAOs. Remember that &vertexArrayObjects[vaoOffset] is a pointer the the start of the range, and the size of the range is model.meshes[meshIdx].primitives.size(). This is important for the next todo:

Call glGenVertexArrays to create new vertex arrays, one for each primitives. For that you will need to pass a pointer to the correct index vertexArrayObjects, which is the size of vertexArrayObjects before it was extended. So you need to store it in a variable before extending its size.

Now we need to initialize each vertex array object in a loop over primitives.

Create a loop over the primitives of the current mesh (so this second loop is inside the first one). Inside that loop, get the VAO corresponding to the primitive (vertexArrayObjects[vaoOffset + primitiveIdx]) and bind it (glBindVertexArray).

Now inside that new loop we will need to enable and initialize the parameters for each vertex attribute (POSITION, NORMAL, TEXCOORD_0). The good news is, the code for each one is the same (we will duplicate it but it can easily be factorized with a loop over ["POSITION", "NORMAL", "TEXCOORD_0"]). The bas news is, we will have many indirections here, so a high potential of errors. Also each attribute is optional, se wo need to get use find on the std::map of attributes, which returns an iterator.

So for this one I will give you the uncompleted code and you need to replace comments starting with TODO with correct code:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | |

VERTEX_ATTRIB_POSITION_IDX of type GLuint with value 0 (the value should be set according to the vertex shader that we use, ie. shaders/forward.vs.glsl, using the corresponding layout(location = ...))

Now that you got it filled, you can duplicate it two times and replace "POSITION" with "NORMAL" and "TEXCOORD_0"; and VERTEX_ATTRIB_POSITION_IDX with VERTEX_ATTRIB_NORMAL_IDX and VERTEX_ATTRIB_TEXCOORD0_IDX (or you can factorized with a loop).

The last thing we need in our inner loop is to set the index buffer of the vertex array object, if one exists. For that you need to check if primitive.indices >= 0. If that's the case then you need to get the accessor of index primitive.indices, its buffer view, and call glBindBuffer(GL_ELEMENT_ARRAY_BUFFER, /* TODO fill with the correct buffer object */)

Set the index buffer of the VAO if it exists.

To finish the function, after the outer loop:

Unbind the VAO, returns vertexArrayObjects. Add a call to your function in run().

Check compilation, run, commit and push your code.

More details about Vertex Array Objects and the global GL state

People generally struggle with Vertex Array Objects when they start OpenGL. glVertexAttribPointer is indeed not really intuitive for a human, since it describes how to convert raw bytes into readable arrays. This is something done by compilers in general, that why we have things like std::vector and not just void*. But in the GPU world we are a bit more low level. This is required to be able to layout our data the way we want, to optimize as much as we want.

Another thing to always keep in mind is the notion of state with OpenGL. We when call glBindVertexArray(vertexArrayObject); we are modifing the OpenGL state, which acts like a big global variable. It's a bit like glBindVertexArray was implemented like this:

1 2 3 | |

and then later call to OpenGL use that global state to act, like if glEnableVertexAttribArray was implemented that way:

1 2 3 | |

Here you can see I am reusing GLOBAL_GL_STATE.currentBoundVao. So if nothing was bound previously, there will be a problem. The same is true if some random VAO has been bound and the code who did this forgot to unbound it after: I will modify it by mistake.

And so finally the most important thing to understand about glVertexAttribPointer: it read two states. It reads the currently bound VAO to modify it,and it reads the currently bound buffer object on GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, to read its id and store it in the VAO. Again, an implementation could look like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | |

So here you see that I am accessing GLOBAL_GL_STATE.currentBoundBufferObjects[GL_ARRAY_BUFFER], and GLOBAL_GL_STATE.currentBoundVao, two fields of the global state.

Why is OpenGL done that way you may ask ? Why does it use so much global states ? Why do we need to keep track of that ? Well probably because of the architecture of early GPUs of history. The OpenGL API has evolved with GPUs and has been designed to fill the need to exploit them efficiently.

Nowadays the architecture of GPUs has changed a lot. That why new APIs like Vulkan have emerged. In the meantime, OpenGL has also evolved and provide new possibilities using extensions. And one specific extension is called "direct_state_access" and offers alternative ways of manipulating OpenGL, with less global state, by directly passing object identifies to functions.

Unfortunately this extension is core only starting at OpenGL 4.5, and I want to keep this tutorial accessible to earlier versions of OpenGL. If you are curious you can start here.